Introduction

The Indian agriculture system is currently unsustainable. A product of the green revolution and subsidized electricity, the cultivation process is highly resource-intensive. The majority of farm holdings in India are small. As per the National Sample Survey Organisation, the average farm size is 1.2 hectares, and the median is lower. 80% of the farmers in India are small and marginal, owning less than 1 hectare of land. Such farmers lose money in agriculture due to high input costs and uncertain returns. The chemical-intensive, mono-cropping style of agriculture is not appropriate to small and patched land-holding as it is impossible to implement economies of scale on such small parcels. It may be well-suited to the large farm sizes of the U.S. from where it originated but it does not make sense for small and marginal farmers of India. Smallholders are afloat as they do not pay for labour, as the entire family is involved in agriculture, and because they consume much of what is produced (Tongia, 2019).

Another challenge that is making matters worse for small and marginal farmers is climate change. 63% of agricultural land is rainfed (The World Bank, 2012), thus the long dry spells, which have become common in recent years, have led to huge rates of crop failure across India. It is ironic that despite India being an agrarian economy with over 50% of the country’s population engaged in agriculture, the country has amongst the lowest yields per hectare for rice and cereal crops. The rice yield of India is a third of China’s and half of Indonesia and Vietnam (The World Bank, 2012). The low productivity is a result of a multitude of factors; patched land holdings, mono-cropping systems, rainfed agriculture, climate change events, lack of awareness about best practices such as seed treatment, heavy use of chemical fertilizers, limited access to farming equipment, and inefficient rural transport system. Feeding the ever-increasing population and sustaining the quality of the environment are two opposing threads that Indian agriculture needs to balance. 80% of India’s cultivable land is mono-cropped with few species, such as rice and wheat, thus threatening genetic diversity and also making farmers more vulnerable to huge losses in case of crop failure. From the viewpoint of the environment, the mounting demand for land for cultivation and water for irrigation is leading to the deterioration of natural systems (Godfray, et al., 2010). Despite these odds, there is a seemingly simple solution to solving the agrarian crisis facing the world and India. Natural and sustainable farming practices have the potential to both enhance productivity and reduce ecological harm. Sustainable techniques in agriculture enable greater resource efficiency, reduce input cost and require less land, water and energy, while making use of locally available materials, thus enabling more profitability for the farmers. These include practices such as crop diversification, multi-cropping, measures to improve soil health, water-use efficiency, seed treatments and various package of practices for different stages of the crop life cycle. Sustainable farming is aimed at better management of the three key elements of agriculture; soil, water and crop. While improving efficiencies in these three areas will boost agricultural productivity, an efficient value chain system providing both backward and forward linkages to farmers is essential for improving farmer incomes.

What do small holders need in today’s time?- Risk Diversification

- Reduced input cost

- Reduced water demand

- Building Climate-resilience

- Synergized Models – Agriculture-Horticulture-Forestry

- Improved Nutrition of households

- Collectivization

- Value Chain Development

Self-Reliant Initiatives through Joint Action is a Non-governmental organization founded in 1997 to evolve innovative solutions in agriculture and livelihoods and scale up the most effective solutions with the help of the government, thereby improving the quality of life of rural communities. Through over two decades of implementation experience in drought-prone and resource-poor villages of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhatisgarh, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha, the organization has devised some best agricultural practices. This compendium aims to share the best practices which have stood the test of time and have worked in different geographies. The best practices that have been covered in this compendium offer the most relevant solutions needed by the farmers in today’s time. While the approaches offered by Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) lead to a reduction of input costs, their main aim is restoring the soil health depleted by years of dumping chemical fertilizers into the soil. CSA when coupled with Multi-tier farmings, helps not only enhance productivity manifold but also provide the diversification that more resembles nature than the banal mono-cropping systems. Another advantage of multi-tier farming is that it provides farmers with cash income throughout the year through staggered harvests. This liquidity is very important for rural farmers who mostly live on credit. Another intercropping system that emerged as a powerful tool to guarantee food security during the hard-pressed COVID-19 times were Poshan Vatikas (kitchen gardens). These miniature backyard gardens not only provided nutritious and colourful meals to rural householders, but the bounty produced was often enough to provide liquidity by the sale of excess vegetables. SRIJAN has been a strong advocate of synergized agriculture models that combine various approaches such as agriculture, horticulture, and silviculture to maximize returns, diversify risks, and most importantly to create nature-friendly systems. Nano orchards are one such approach aimed at making fruit tree cultivation a possibility for small and marginal farmers. Horticulture has always been seen as a big farmer’s choice. SRIJAN’s customized nano orchards are dense plantation models requiring only a fourth of an acre while giving a return of an average of Rs.70,000 a year from the fourth year onwards. Similar to Nano orchards are Miyawaki, which are dense plantations of indigenous forest species on 0.1-acre land patches. Propagated by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki in the 1980s, this method is the quickest way to afforest denuded sites. SRIJAN is promoting Miyawaki adoption in rural areas as a means to check the rapid deforestation in the country’s hinterlands, which is leading to unprecedented loss of soil and moisture and adversely affecting the local water table thus ultimately affecting the primary livelihood of rural households; agriculture. Another innovative model that has been documented in this compilation is the Soya Samriddhi. A set of crop-specific best practices which when combined with a meticulous outreach programme led to incremental yields in the range of 30-50% for soy farmers in the Bundi district of Madhya Pradesh. The programme was able to reach over 40,000 farmers across Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan in a matter of 6 years. We hope that these best practices can be replicated along the length and breadth of this nation with the help of government and non-government organizations and that this document serves as a reference for practitioners and policy-makers alike.

Bibliography

- Godfray, C., Beddington, J., Crute, I., Haddad, L., Lawrence, D., Mules, J., . . . Robinson, S. (2010). Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science, 812-828.

- The World Bank. (2012, May 17). India: Issues and Priorities for Agriculture. Retrieved from The World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/05/17/india-agriculture-issues-priorities

- Tongia, R. (2019). India’s Biggest Challenge: The Future of Farming. The India Forum.

Nano Orchards

Introduction (Why)

Input-intensive, mono-cropped agricultural systems are becoming an increasingly risky investment for small and marginal farmers with limited resources. Even today, 60% of the agricultural land is rainfed. The uncertainty associated with monsoons is exacerbating with each passing year due to climate change. Long dry spells between two successive monsoon showers are leading to crop failure even in rainfall sufficient years. This is making mono-cropped Kharif agriculture a gamble for most smallholders. Most smallholders cultivate only Kharif crop due to lack of resources and increasing expenditure of traditional agriculture systems. The production is often used to meet household consumption needs. Livelihood for the rest of the year is ensured by migration to towns and cities for unskilled labour work. Perpetual poverty and malnutrition are the consequences of such vulnerable livelihoods. To make agriculture profitable for smallholders, it is pertinent to shift to diversified cropping systems such as; horticulture, agro-forestry, vegetable cultivation, or a combination of these, to allow for farmers to hedge risks and make agriculture climate-resilient.

Nano Orchards (What)

Horticulture has, forever, been seen as a ‘big farmer’s choice’, due to high initial investment, need for an assured source of irrigation and risk of plant mortality. However, it can serve as a good option to hedge and diversify risks of monocropped agricultural systems, if undertaken strategically.

SRIJAN has over the last decade conceptualized, piloted, and scaled-up, ‘Nano Orchards’, in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan. Nano orchards are high-density horticulture models wherein; 40-60 fruit plants are cultivated as the main horticulture crop, along with a short-duration horticulture crop or vegetables as the intercrop, in a 0.25-acre land. These nano orchards have been customized for small-holders for diversifying their farm income. This Nano orchard model gives the same returns, as the 1-acre classic, in a fourth of the land space. SRIJAN has decisively changed the perception that Horticulture is for big farmers, by training farmers in canopy management, simplified Package of Practices (POPs), and diversification of fruit crops.

Evolution of Nano Orchards (the story of origin)

In the 1980s, the classic model of promoting fruit-tree farming among small and marginal farmers. Designed to be developed on 1-acre of land, the classic model was suitable for small farmers then as the landholding in 1980-81 was 1.84 hectares. A large number of farmers have benefitted from this scheme across the nation. Over two decades have passed since the classic model was first adopted. The average farm size has shrunk to almost half of that in 1980. As per the agriculture census 2015-16, average land-holding stands at 1.08 hectares. Due to this drastic reduction in land-holding most small and marginal farmers are unable to practise horticulture as they are reluctant to lock in a majority of their landholding for horticulture. The need for a customized model for small farmers was thus felt, which required a smaller land parcel to develop fruit orchards. The professionals working with SRIJAN realized this when they were implementing the classic orchard projects in the Chhindwara and Annupur districts of Madhya Pradesh in 2010. Based on their learnings and insights, SRIJAN professionals developed a 0.2 acre model of fruit-tree plantation which could accommodate 40 to 60 saplings of different fruit trees by planting in a high-density model. The number of fruit trees planted was the same as under the classic model, but the spacing (plant to plant and row to row) was reduced to enable the farmers to earn the same amount of income from a smaller land parcel. These orchards were named, ‘Nano’, apt to the minimal space occupied by them. The nano orchards were piloted in the Tikamgarh and Annupur districts of Madhya Pradesh in small numbers. In the year 2017, a breakthrough occurred in the form of dedicated funding from Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives (APPI) that allowed internal scale-up of Nano orchards in 3 of SRIJAN’s implementation states; namely Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. Four identified livelihood clusters in these states came up with contextual nano orchard models based on the type of soil, availability of water, individual landholdings, and interest in cultivation.

The various Nano orchard models that emerged as a result of the project are summarized below:| State | Livelihood Cluster | Nano Orchard area | Main horticulture crop | Intercrop |

| Rajasthan | Pratapgarh and Pali | 0.2 Acre | Guava (60 plants) | Papaya (50 plants) |

| Madhya Pradesh | Jatara and Jaisinagar | 0.2 Acre | Pomegranate (80 plants) | vegetables |

| Madhya Pradesh | Chhindwara | 0.15 acre | Guava (50 plants) | |

| Chhattisgarh– | Koriya | 0.15 acre | Mango (40 plants) | |

| Madhya Pradesh | Kotma | 0.15 acre | Mango, Pomegranate & Guava (40 plants) | Mixed cropping of any two main horticulture crops |

Setting up a Nano Orchard (How)

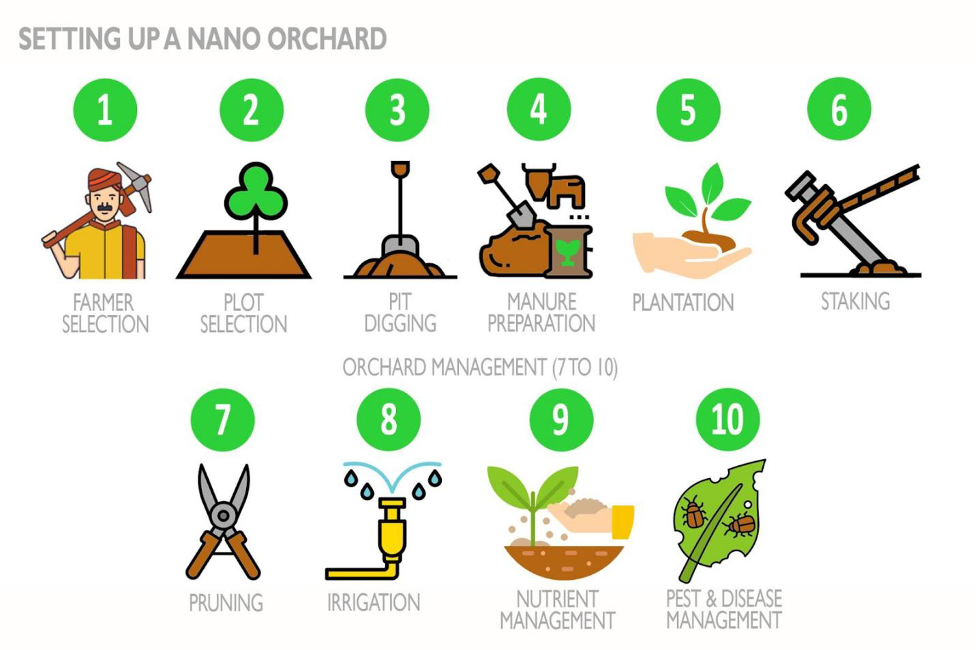

To set up a Nano orchard, the first step is the selection of an interested farmer with a minimum landholding of 0.5 acres who have assured access to irrigation. Post farmer selection, a series of inputs in the form of quality saplings, training, and capacity building is undertaken by SRIJAN to ensure the successful setting up of a Nano orchard. The key steps involved in setting a Nano orchard are explained in the infographic that follows. The implementation process is elaborated on below.

- Farmer and Plot Selection: Interested and willing small and marginal farmers with a minimum landholding of 0.5 acres with an assured source of irrigation are selected for setting up nano orchards. Post this, a plot of land having a gentle slope and fertile soil is selected. It is generally preferred that the plot of land be in the backyard of the farmer’s house for ease of watering, manuring, and regular monitoring.

- Pitt Digging: The first step is setting up a layout of the plot. If the plot is not rectangular, a 90-degree layout is designed. Also, it is necessary to leave a space of 3 metres on all four sides of the plot to allow for branches to spread out. Pits are dug keeping in mind crop-specific, plant to plant, and row to row distance. 3 x 4.5 m for Pomegranate, 3 x 4 m for Guava, and 4 x 4 m for Mango. Pit dimensions also vary as per the horticulture crop selected. For pomegranates, pit dimensions are 2X2X2 ft, 2.5X2.5x2.5 ft for guava, and pits measuring 3X3X3 ft are dug for mango. The topsoil and bottom soil dug out from the pit are kept separately in different directions of the pit.

- Manure Preparation: Pit filling is done 45 days after pit digging. The excavated soil is sun-dried to kill harmful bacteria and pathogens. The topsoil is filled in the pit first forming the bottom layer of the pit. The bottom soil is mixed with 15 kg of farmyard manure, and 1 kg organic pesticide such as neem cake and filled into the pit.

- Plantation: Grafted saplings of age between 1 to 2 years are planted in the orchard. The minimum height of the sapling should be from 1 – 3 feet. The sapling should be checked for cuts in roots and knotted roots, as both are not suitable for planting. The plantation should be undertaken preferably in the monsoon season or in the first week of February. Sapling should be planted by digging around 9-12 inches at the centre of the filled pit after removing the polybag of the sapling with a razor. The sapling should not be handled by the stem.

- Staking: Staking protects the sapling from direct wind and gives stability to its roots. From the centre of the plant, stakes should be 1.5-2 feet apart with two parallel and one horizontal stick. The plant should not be tied with wire to the stake but rather with a soft rope through an 8-shaped pattern, with one part on the plant and the other on the horizontal stick.

Orchard Management

- Pruning: Pruning is done to strengthen the main stalk and promote branching and allow the tree to grow in a bowl shape. The branches growing inwards should be chopped completely and those growing outwards at the top. Light pruning is to be done in the initial year and heavy pruning post 1 year. Pruning should be done such that sunlight is not obstructed for any branch.

- Irrigation: Fruit crops do not require a lot of water but they do require moisture continuously. Cost-effective methods such as drip, pitchers, mulching, etc. ensure proper moisture maintenance.

- Nutrient Management: Every 15 days, Jeevaamrit (a mixture of cow urine, cow dung, jaggery, gram flour, and water) should be applied to promote plant growth. Six months after plantation, azotobacter should be applied with vermicompost in the plant ring, and one-year post plantation, organic manure preparation should be applied. Post this Farm Yard Manure (FYM) or vermicompost should be applied every six months.

- Pest and Disease Management: Application of neem cakes should be done while the plantation stage and then at regular intervals of 6 months. The plants and leaves should be regularly checked for signs of disease and appropriate measures should be taken to prevent the spread of the disease.

Reach (Where)

The Nano orchards promoted by SRIJAN are operational in 10 districts spread across four states of the nation. The reach has been tabulated below: (This can be illustrated through a map)| State | District | Block | Horticulture Plant | No. of Nano orchards |

| Madhya Pradesh | Anuppur | Kotma, Anuppur | Pomegranate, Mango, Guava | 470 |

| Madhya Pradesh | Shivpuri | Karera | Guava | 163 |

| Madhya Pradesh | Chhindwara | Chhindwara, Mohkhed, Sausar | Mango, Guava | 437 |

| Madhya Pradesh | Tikamgarh | Jatara, Palera | Pomegranate, Guava | 236 |

| Rajasthan | Karauli | Mandrayal | Guava | 40 |

| Rajasthan | Pratapgarh | Arnold, Peepalkhot | Guava | 196 |

| Chhattisgarh | Koriya | Manendragarh | Pomegranate, Mango | 207 |

| Chhattisgarh | Jashpur | Bagicha | Mango | 30 |

| Total | 1779 | |||

Cost and Benefits

The set-up cost of a Nano orchard is a one-time investment, with maximum expenditure occurring in the first year. Post the first year, some expenditure is needed on manuring and growth boosters. Post the initial years, after the tree has been firmly established, it needs minimal inputs. In the first year of the plantation, the cost of cultivation for 0.25 acres of land is between Rs. 35,000-Rs.40,000, while from the second year onwards the cost reduces to Rs.2000-3000 per year incurred upon providing nutrition, manuring and pest management. The returns expected from horticulture plants vary year on year. In the initial years (3 years after plantation) the farmer can earn an income ranging from Rs.10,000- Rs.40,000. From the 5th to 7th year after plantation, annual income could range from Rs. 40,000-Rs.70,000. And post that for the next 8 years, (assuming a life of 15 years), a farmer can earn an average income of Rs.1,25,000 per year from a fourth of an acre through horticultural cultivation.Convergence

Extensive efforts for collaboration and convergence have been made by SRIJAN to maximize knowledge dissemination, and access to relevant schemes and programs of the government, which allowed for faster adoption of Nano orchards among small and marginal farmers. Collaboration with crop-specific research universities was done for improving the technical capabilities of farmers. National Research Centre on Pomegranate (NRCP) provided crucial inputs regarding the package of best practices to the pomegranate orchard farmers in Madhya Pradesh. Similarly, Central Institute for Subtropical Horticulture (CISH) was collaborated with for Mango and Guava orchards. They provided constant support in the form of training, exposure, and interface during critical stages of the crop cycle. These collaborations not only helped in providing technical strength to the nano orchards programme but also added credibility in demonstrating the model to the district administration and other potential stakeholders. SRIJAN attempted to merge the programme with relevant line departments of the government to support farmers through asset creation, productivity enhancement, and labour payments. Horticulture and Agriculture departments along with MGNREGA were clubbed in Annupur district to provide multiple support systems. Water sources in the form of farm ponds or wells were developed under MGNREGA, while farmers were linked with Nandhan Fal Yojana, which supports farmers in setting up fruit orchards and vegetable farms by the provision of labour payment to farmers for working in their own orchards. A labour payment of Rs. 870/plant/year for three years is given for orchard maintenance and management to farmers under the scheme, provided the orchard has more than 80% plant survival rate. SRIJAN entered an MOU with Zila Panchayat in FY 2016-17 in Madhya Pradesh to facilitate linkage with the said scheme. In monetary terms, the MOU led to a convergence of over Rs. 99 crore benefitting 12,163 farmers in Chhindwara, Shivpuri and Annupur districts.Major Learnings

- The low land requirement was one of the major factors which encouraged a large number of farmers to adopt Nano orchards. As the land requirement is as low as a backyard kitchen garden, many small and marginal farmers used their homestead land for developing nano orchards.

- There is no one-size-fits-all. SRIJAN has over the last decade of experimentation with Nano orchards realized that contextualization in the selection of the fruit crop to be planted is necessary, based on the type of soil, water availability, and other agro-ecological factors for the orchards to be successful.

- The first few years (2-3 years) until the tree is firmly established, are the most crucial. If adequate nutrition and water are available to the nano orchard at this time, the probability of success of the plantation is very high. To ensure that the orchards don’t fail, SRIJAN took special efforts to ensure irrigation in the summer months. The organization equipped farmers with bullock carts installed with plastic drums (1100 litres capacity). Farmers would fill these drums and irrigate their orchards on a rotation basis. Most small farmers without a perennial source of irrigation, found this to be a convenient way to bring water to their horticultural plant. The organization also facilitated the creation of irrigation assets such as farm ponds and dug wells through linkage with MGNREGA for small farmers.

- Most small and marginal farmers refrain from practising horticulture, as it is a long-term crop. Being risk-averse and wanting to secure their consumptive requirements, such farmers prefer food grains over fruit trees. To overcome this obstacle, SRIJAN promoted intercropping of vegetables and short-term fruits (papayas) between the main horticulture plant. This allowed farmers to earn some income in the initial years before the trees started bearing fruit.

Scale-up potential

Given the rising number of small and marginal farmers with less than 1 hectare of land holdings, it is imperative to shift from the traditional cereal-based, input-intensive, climate-vulnerable, monocropping systems to multi-cropping systems. Migration income is an unsustainable way to fund agricultural losses and cannot be accepted as a viable solution if poverty is to be addressed. In such a scenario, models such as Nano orchards present viable and practical solutions, which can be scaled up nationally. Their limited land requirements, low-input intensive, and climate-hardy nature make them a good solution, which along with enhancing incomes, also provide nutritional security to households. SRIJAN initiated Nano orchard pilots a decade back in 2009 in Tikamgarh and Annupur districts of Madhya Pradesh and in the last 10 years, internally the organization has scaled up the programme in 10 districts of four states, with the help of private donors and the government. A Civil society organization (CSOs) functioning in limited geographies has its constraints. Collaboration and adoption of the model by other CSOs and the government will truly lead to a scale-up of the intervention at the national level. A small step has been taken in this direction by district administrations of Chhindwara and Annupur districts, who intend to develop 10,000 nano orchards in the two districts with technical and knowledge support of SRIJAN.Climate-Smart Agriculture

Introduction (Why)

Traditional agriculture witnessed a paradigm shift in India during the 1960s. Then, India was a food-scarce nation, and to ensure food security, the government promoted input-intensive agriculture widely popularized by western countries. Green revolution paved the way for increasing production manifold primarily by deploying expensive chemical inputs and hybrid seeds. Due to this, our nation achieved food security by the 1970s. Despite this fact, 89.2 million people are undernourished in India as per Food and Agriculture Organization estimates. This makes 14% of the population of the country.

By 2050, the Indian population is estimated to reach 1.7 billion people which will make India the most populous country in the world, and the food demand is expected to increase by 70%. Already, the limited land resources of the country are in a state of degradation and deterioration. According to the Desertification and Land Degradation Atlas 2018 prepared by the Indian Space Research Organization, 30% of the country’s landmass is undergoing degradation. As the soil deteriorates, the yields of farmers are declining despite increasing the spending on chemical inputs and genetically modified seeds. This input-intensive approach of farming has indebted millions of small and marginal farmers. The situation has been exacerbated due to agriculture’s vulnerability to climate change, the impacts of which are being felt in the form of increasing temperatures, shifting agro-ecosystem boundaries, weather variations, invasive crops and pests, and frequent extreme weather events. This has negatively impacted crop yields and lowered the productivity of livestock. Climate change is making input-intensive agriculture a loss-making bargain due to the increased uncertainty of good harvests. The green revolution was a good short-term solution to the food crisis of the country, but it has proved to be a bane for small and marginal farmers in the long term. The excessive use of chemical inputs has not only deteriorated soil, but also indebted farmers and led to making agriculture a net emitter of Greenhouse gases. A shift from the current system of agriculture is thus warranted to; a) meet the enormous food demand, b) make agriculture profitable for smallholders, and c) make agriculture resilient to increasing climate change threats.Climate-Smart Agriculture (What)

Climate-smart Agriculture (CSA) is a holistic approach to managing croplands developed to tackle food security as well as climate change challenges by going back to organic methods of cultivation which were practised before the industrialization of agriculture.

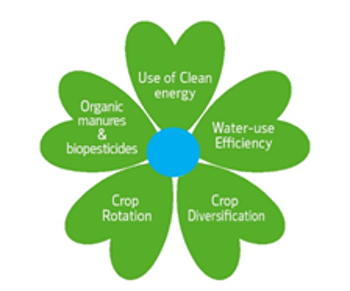

The three pillars of the Climate-Smart Agriculture Approach are; i) Sustainably increasing productivity and income, ii) Strengthening resilience to climate change, and iii) Reducing agriculture’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. The various practices promoted under Climate-smart agriculture are multi-cropping, inter-cropping, crop rotation, use of organic fertilizers and biopesticides, water-use efficiency, and promoting the use of solar energy for irrigation. Self-Reliant Initiative through Joint Action (SRIJAN) has been working with small and marginal farmers in the drylands of the country to increase productivity and enhance incomes from patched land-holdings. In recent years, the organization initiated focussed efforts to build the climate resilience of rainfed small landholders by promoting various sustainable agriculture practices. Over the last 4-5 years, the organization has evolved a comprehensive Climate-Smart Agriculture approach. The present case will discuss the nuances of this approach and its impact on farmer-beneficiaries.

Implementing Climate-Smart Agriculture (How)

The aim is to eliminate the risks of chemically cultivated mono cropped systems, as these entail negative impacts upon a small farmer’s finances as well as health & well-being. SRIJAN promotes Climate-Smart Agriculture in its programme areas by developing innovative farmers as prakritik entrepreneurs. The prakritik entrepreneur selected is trained to make organic inputs in the form of fertilizers, growth boosters, and insecticides. The farmer is supported to set up a Prakritik Krishi Kendra (Natural Agriculture Unit), which enables the farmer to collect cow dung and urine effectively and develop organic inputs for farms. The entrepreneur is tasked with the work to promote Climate-smart practices in his village. This innovative farmer not only applies the organic inputs but also adopts other Climate-smart practices such as crop diversification, multi-cropping, water-use efficiency, etc. on his farm. S/he also maintains a demo plot to undertake experimental trials of new varietals and methods. The farmer thus emerges as a role model in his village, whom fellow farmers gradually start emulating, and thus the Climate-smart agriculture practices are adopted by other farmers.

The major steps to promote Climate-smart Agriculture adopted by SRIJAN are as follows:

The major steps to promote Climate-smart Agriculture adopted by SRIJAN are as follows:

- Identification of an innovative farmer

- Setting up Prakritik Krishi Kendra

- Farmers’ meetings and capacity building

- Dissemination of Climate-Smart agriculture practices

- Farmers’ collective

Identification of an innovative farmer

SRIJAN conducts regular meetings with villagers to discuss challenges facing rural livelihoods and to find solutions to these. The personnel often provide information about best agriculture practices that will help maximize productivity. Some farmers adopt the practices faster than others. The organization works on the strategy of promoting climate-Smart role models for Climate-Smart Farming. Also, over the years of working in rural landscapes, it was seen that the best adoption rates were a result of shared learnings of community through the emulation of torchbearers.SRIJAN has well-defined criteria for the selection of a farmer as a prakritik entrepreneur:

- A progressive farmer

- Innovator and risk-taker

- The landholding is more than 1 acre

- Owns atleast 5 cows

- Willing to develop a 1-acre plot as a demo plot

- Good rapport in the community

Setting up Prakritik Krishi Kendra

A natural farming unit or a Prakritik Krishi Kendra is set up on Prakritik entrepreneur’s premises to provide her/him with the tools to manufacture organic inputs with ease. The key ingredients of organic fertilizers and other inputs are cow dung and cow urine. The cattle shed of the farmer is provided with concrete flooring and proper drainage along with a sturdy shed roof, and proper ventilation. Fodder and watering containers, drums, and plastics for storing the organic concoctions are provided. Green fodder seeds are also provided so that the farmers can ensure adequate food for their cattle. The cattle undergo a health check-up and are provided with the necessary vaccinations to prevent them from common diseases. The prakritik entrepreneur is trained to develop organic fertilizers such as Ghanjivamrit and Jivaamrit. These are organic manures made by mixing cow dung, cow urine, soil, gram flour, and jaggery. The entrepreneur is also guided to develop various biopesticides and growth boosters such as Panch Patti Kada, Soya growth booster, neemastra, etc. Post the set-up of the Prakritik Krishi Kendra and the requisite training, the entrepreneur concocts different organic inputs mentioned above and uses them on his farms as well as distributes them to other farmers of the village for demonstration purposes. After the efficacy of the organic inputs has been well established among the farming community of the village, the entrepreneur will charge for the organic inputs provided by him. Along with manufacturing organic inputs, the entrepreneur maintains 1-acre of plot land for demonstration. Herein the farmer experiments with improved crop varietals, and crop-specific packages and practices. This demo plot acts as a tool for knowledge transfer and capacity building of farmers as humans are known to learn best by observing. The ultimate aim of the natural farming unit is to facilitate knowledge transfer through field-level demonstrations and to provide farmers with organic inputs at a reasonable price. The unit can be thought of as a living laboratory where farmers learn from each other through shared experiences and experimentation.Farmer’s meeting and Capacity building

The natural farming unit plays a key role in building the capacities of farmers on climate-smart agriculture practices. The farmers conduct regular meetings at the Prakritik Krishi Kendra. Four meetings are planned both for Kharif and Rabi cropping seasons, which are meant to transfer knowledge during critical crop growth stages. Pre-sowing training informs the farmers about land preparation. This is the stage where the organic fertilizers developed at the natural farming unit play a key role. The second training known as Post sowing training provides information on weed management, irrigation requirement, and the use of natural growth boosters to improve plant growth. The third training revolves around insect and pest management through natural means such as biopesticides and sticky traps. The final training on post-harvesting operations, is related to moisture prevention, proper harvesting and storing of produce, and collective marketing for best returns. Apart from these meetings, the farmers also meet regularly to share experiences and learnings. The demo unit plays a crucial role in the dissemination of an improved package of practices for specific crops.Dissemination of Climate-Smart Agriculture Practices

The Climate-Smart Agriculture practices promoted by SRIJAN affect every stage of the crop growth cycle and attempts to incorporate the use of locally available natural inputs into all aspects of crop management.

The following package of practices is promoted under climate-smart agriculture

- Desi (indigenous) seeds are promoted over genetically modified variants. Seed treatment with Bijamrit is promoted. 1 litre of bijamrit is sufficient to treat seeds to be sowed on an acre of land

- During the pre-sowing stage, land preparation with organic inputs is given huge impetus. Ghanjivamrit and Jivamrit, the organic fertilizers prepared at the natural farming unit applied to the field. 108 kg of Ghanjivamrit and 10 litres of Jivamrit are required per acre during the land preparation phase.

- Line-sowing is promoted to enable optimum utilization of resources.

- Intercropping with pulses in place of monocropping of cereals and rice, multi-cropping systems with vegetables and fruits, and nano orchards are promoted to enable farmers to diversify the risk of crop failure which is much higher in mono-cropped systems.

- Farmers are encouraged to practice water-use efficiency measures such as alternate furrow irrigation, raised bed cultivation, and installation of drip systems.

- The harvesting phase focuses upon training on moisture prevention and maintenance of proper storage conditions.

- Farmers’ collectives such as Farmer Producer Organizations benefit the farmers by providing them bargaining power. In the case of chemical-free food production, it may also lead to premium pricing of their produce. Towards this end, SRIJAN has promoted six FPOs in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

The Climate-Smart Agriculture Model

The Climate-smart agriculture model of SRIJAN rests on the cluster-based approach, wherein a Prakritik Krishi Kendra is set up at the gram panchayats level. It functions on a 3-tier approach represented below:

- Farmers procure organic inputs and knowledge about climate-smart agriculture practices through the medium of Prakritik Krishi Kendra of his village

- The Prakritik Krishi Kendra serves the farmers in this catchment area. It acts as a hub for knowledge transfer, shared learning and experimentation, and provision of organic inputs and quality seeds. Each unit is estimated to serve 80 farmers in the first year of its establishment and will eventually expand its reach to cover 300+ farmers by the fifth year of operations. These kendras are managed by prakritik entrepreneurs, who will provide bio-stimulants, and sell quality seeds to farmers. Initially, SRIJAN provides support in the establishment of infrastructure and operational costs but eventually the entrepreneur is expected to become self-sufficient and even earn profit from the sale of organic inputs.

- The Farmer Producer Organizations act as an overarching body that provides forward as well as backward market linkages, information dissemination and value-addition of production.

Reach (Where)

Climate-Smart Agriculture programme is currently being implemented in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh.7220 farmers have adopted one or the other climate-smart practice bringing under 3485 acres under CSA. The use of organic inputs has the highest rate of adoption. Farmers use organic fertilizers and bio pesticides provided by 39 Prakritik Krishi Kendras, which have produced 13,878 quintals of organic manure.Cost and Benefits

The cost to set up a Prakritik Krishi Kendra is Rs. 29,000, of which 20% is contributed by the prakritik entrepreneurs. The prakritik entrepreneur provides land on which to construct/modify the cattle shed and also provides 1-acre of land as a demo plot. The expenditure incurred on making the biostimulants is incurred by the entrepreneur. The cost of making Ghanjivamrit and jivamrit is Rs. 5/kg and Rs. 7/litre, while the entrepreneur sells Ghanjivamrit for Rs. 7/kg and jivaamrit for Rs. 10 per litre. The estimate of Income and Expenditure for the entrepreneur is below:| Income and Expenditure estimate for Ghanjivamrit | |||||

| Year | No. of farmer served | Qty* (in kg) | Cost | Income | Profit |

| Year 1 | 80 | 8000 | Rs. 40,000 | Rs. 56,000 | Rs. 16,000 |

| Year 2 | 160 | 16000 | Rs. 80,000 | Rs. 1,12,000 | Rs. 32,000 |

| Year 3 | 240 | 24000 | Rs.1,20,000 | Rs. 1,68,000 | Rs. 48,000 |

| Year 4 | 320 | 32000 | Rs. 1,60,000 | Rs. 2,24,000 | Rs. 64,000 |

| Year 5 | 320 | 32000 | Rs. 1,60,000 | Rs. 2,24,000 | Rs. 48,000 |

| *quantity of Ghanjivamrit is estimated based on the requirement for 1 acre of land. 108 kg of Ghanjivamrit is required per acre area | |||||

Impact

- Farmers save approximately Rs. 1500-2000/acre of land by replacing Urea and DAP with Ghanjivamrit and Jivamrit.

- Climate Smart farmers also save on the cost of hybrid and genetically modified seeds, as they use desi seeds.

- Within a year of initiation of the programme, the number of farmers who have adopted Climate-smart farming has increased from 100 farmers to 7220

- In the case of the adoption of intercropping and multi-cropping systems such as multi-tier farming, the farmers have reported an improvement in income from agriculture.

Major Learnings

- The rate of adoption of organic inputs was higher in this approach as observed by SRIJAN. One of the reasons attributed is that since the hassle of collecting cow urine and making organic fertilizer is removed due to the services of the prakritik entrepreneur, the farmers have made the switch to organic with ease.

- The model of promoting Prakritik entrepreneurs which leads to intensive engagement with one progressive farmer per village and extensive engagement with the other farmers has led to faster replication as farmers have been noted to replicate each other’s practices better. The previous model where one person from the organization was tasked with reaching out to all programme farmers in n number of villages was more time consuming as well as it had been seen to dilute the quality of work, as the number of farmers increased.

Next Steps

-

Organic Certification

-

Seed Hub

Replication and Scale-up potential

The Climate-Smart Agriculture model of SRIJAN is based on both deep and light touch approaches. Under the programme, the organization provides intensive support to the Prakritik entrepreneur and extensive support to the other farmers practising CSA. This approach is effective as the effort required to train and develop one model farmer per village is relatively less than covering a large number of farmers. The trained farmer is responsible for enabling the adoption of practices by other farmers. This way the organization has been able to scale up the project internally to all its programme states. This represents replication potential by other organizations too. If government encourages farmers to go organic (as some states have done, notably Sikkim), the CSA model has a good scope of national scale-up.Multi-tier farming

Introduction (Why)

The average landholding of Indian farmers is declining with the increase in population as the limited land resource is being passed on generation over generation. As per the agriculture census 2015-16, the average land-holding stands at 1.08 hectares (2.6 acres) with small and marginal farmers accounting for over 85% of landholders in the country. Industrialized nations popularized the concept of input-intensive mono cropped farming across the globe, setting up firm roots in India with the green revolution in the 1960s. Major agrochemical giants entered the Indian market with the promise to quadruple yields, and aggressively promoted chemical fertilizers, often prescribed in exaggerated proportions, backed by government support. Small and marginal farmers embraced this method of farming, which entrenched them in a perpetual cycle of debt, and the debt burden of a father was passed to his son, as an accompaniment to the ancestral landholdings. Small and marginal farmers have meagre and patched land holdings, and the primary reason that input-intensive, single-crop cultivation is not suitable for them is that over 60% of agricultural land even today is rain-fed. This monsoon dependency makes the crop vulnerable to high rates of failure. Investing highly into inputs put farmers in debt as most inputs are Multi-cropping systems provide a safety net as they allow the farmer to diversify the crop failure risk and ensure optimum use of the limited resources at the farmer’s disposal. Multi-tier farming is a multi-cropping system that is best suited for small and marginal farmers as it offers the benefits mentioned above and requires minimal space for set-up.Multi-tier farming (What)

Multi-tier farming is a method of cultivating compatible plants of different heights on the same plot of land by sowing at varying depths of soil. It is most suitable for small and marginal farmers, who can compensate for lesser landholdings by using vertical space more effectively. It calls for optimum utilization of resources; solar energy, water, manures and fertilizers and results in higher yield per unit area. Multi-tier farming is a great tool for maintaining liquidity which is an important need of small and marginal farmers, who live on credit from one crop cycle to another. Multi-tier farming leads to a staggered harvest, meaning that since crops with different maturation duration are planted together, the multi-layer farm churns out fruits and vegetables round the year, thus leading to a more evenly distributed income. Other benefits of multi-tier farming include;- Vegetables, fruits and pulses grown in a multi-tier farm complement each other in terms of provision of canopy cover and shade, litter, improved soil moisture levels and enriching micronutrients.

- It ensures nutritional security for members of the household and also saves the expenditure incurred upon vegetables.

- The risk of pest attacks is greatly reduced due to multiple cropping which includes plantation of trap plants such as marigold.

- High plantation intensity leads to reduced weeding instances and hence saves time and labour for farmers.

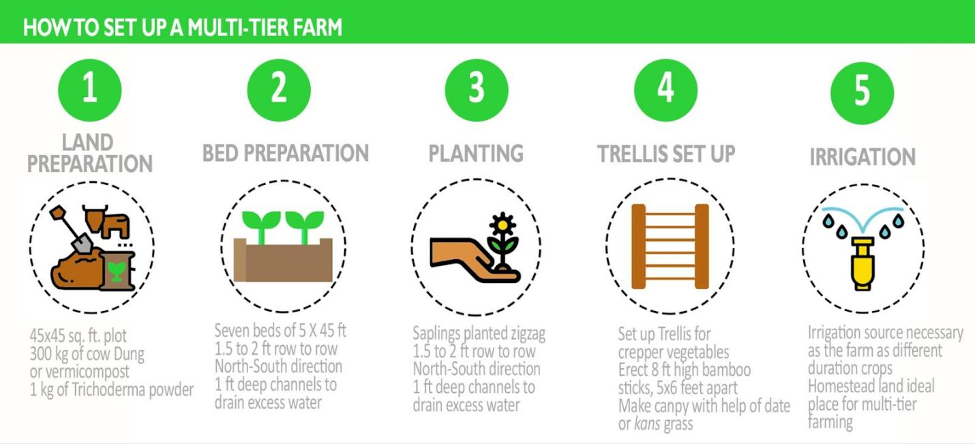

Setting up a Multi-tier farm (How)

After identification of a suitable land parcel; preferably homestead land close to the family’s house, different crops are selected as per their growth duration to allow adequate sunlight. The crops selected have different harvest cycles which help the household have continuous cash flows and nutritional security throughout the year. Sowing is done strategically to allow different vegetable and fruit crops to grow in the same land parcel. The major steps involved in Multitier farming are presented through the infographic below:

- Land preparation: Land which has some slope and fertile soil is suitable for multitier farming. The selected land parcel is prepared by depositing organic fertilizer, either farmyard manure or vermicompost and Trichoderma powder.

- Raised beds for plantation: After this, raised beds are prepared. Channels are dug in the field to allow for excess water to drain off.

- Planting and sowing: This is followed by strategically planting or sowing the fruit tree and vegetable combinations selected in a zig-zag manner

- Trellis set up: A wooden trellis is set up atop the plot to allow for creeper vegetables to climb. 8 ft tall bamboo poles are erected 5x6 ft apart in the farm. The canopy is made by thatching leaves of date or kans tree.

- 5. Irrigation security: A crucial requirement of multi-tier farming is an assured source of irrigation, as it is a high-density plantation model.

Selection of vegetable & fruit combinations

What to plant in a multi-tier farm?

The bottom tier or the ground floor is formed of tubers such as ginger and turmeric, the first tier/floor of herb crops such as spinach and coriander. The second tier is made up of vegetables such as tomatoes, chilli, eggplant and capsicum, etc. Creepers of the gourd family make up the third floor, while the fourth layer is made up of fruit trees such as papaya. Strategic sowing and planting of crops is of utmost importance as the placement affects the amount of sunlight received. Saplings are planted in a zig-zag manner in rows to allow each sapling its due share of resources. Sowing is directly done for creeper vegetables and tubers. After sprouting, weak seedlings are removed. Grown-up seedlings of creepers are supported by homemade trellis. High-density multilayer farming also has fewer weeding instances, as existing crops make optimum utilization of water, nutrients and sunlight. The amount of fertilizer and manure needed in cultivating four or more crops is the same as that of cultivating one crop, making the cost of cultivation lower and the income higher than monocropping systems.Season-wise vegetable-fruit combinations of Multi-tier farms

| Sowing period | Ground Layer | First Layer | Second Layer | Third layer | Fourth layer |

| June-July | Turmeric Ginger | Musk melon Cabbage | Eggplant, Tomato, Chilli | Bottle gourd, beans, ridge gourd | Papaya |

| August-September | Potato, Onion, Radish, Carrot, Garlic | Coriander, Fenugreek, Cabbage, Cauliflower, Broccoli | Cluster beans, Peas | Bottle gourd, beans, ridge gourd, Pumpkin, French beans, pointed gourd | Papaya |

| October – December | Potato, Onion, Radish, Carrot | Coriander, Fenugreek, Spinach, Amaranth, Cabbage, Cucumber, Watermelon | Peas, Tomato, Eggplant, Chilli | Bitter gourd, bottle gourd, ridge gourd | Papaya |

Reach (Where)

Multi-tier farming is being practised in Madya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan. 206 families have set up multi-tier farming plots since 2019. The average harvest from a multi-tier farm is 12 quintals of different vegetables/fruits and the average income earned is Rs. 25,000Cost and Benefits

The total cost to set up a multi-tier farm on a 200 sq. mt. plot is Rs. 21,235. SRIJAN provides the bamboo poles and wire for setting up the trellis and input support in terms of seeds. The community contributes by providing the labour required for setting up the farm and the trellis, preparing and application organic manure, and ensuring irrigation. The community contribution accounts for 50% of the total cost. The expected income from a 200 square meter multi-tier farm planted with 5 layers of crops is Rs. 50,000Convergence

As the intervention is very recent, (SRIJAN initiated its experiences with multi-tier farming in 2019), the organization has had limited chance to leverage government schemes. Some beneficiaries have been provided weeders and sprayers through linkage with agriculture department schemesMajor Learnings

- Knowledge transfer on the package of practices should be done thoroughly for the successful establishment of a multi-tier farm. The first year is crucial as the farmer is not only learning about the layout and spacing of the plethora of crops to be cultivated in a small area but also about the different package of practices of manuring and managing pests of different crops.

- The erection of a proper trellis is crucial for the success of the multi-tier farm. If the required number of poles are not used to build a trellis, it might not be effective in terms of shade provision and the management of creepers might become cumbersome.

- It is crucial to select farmers carefully for multi-tier farming as it is a labour-intensive time-consuming method of farming that requires constant upkeep for its success.

- It is pertinent to develop a comprehensive season-wise list of compatible and complementary crop combinations for sharing with farmers to ensure optimum production and nutrient management.

- Proper modular training and extension material on natural and organic methods of pest management was felt as multiple crops, each with its own set of pests, were cultivated together.

- Border plantation of marigolds and the use of sticky traps proved to be effective in keeping most common insects at bay. Both these proved to be low-cost high-impact practices.

- Another pertinent observation was that promotion of the same set of crops in a village led to an abundant supply of one vegetable and this led to farmers getting lower prices for their produce. It is thus pertinent to promote different crop combinations with different sets of farmers to ensure diversity in vegetable supply.

Scale-up potential

The scale-up potential of multi-tier farming is huge. Along with ensuring food and nutritional security of small and marginal farmers, it is also better resilient to climate-change events and hence better adapted to today’s climate-vulnerable world. Other features which make it scalable are; faster turnaround than food crops, the requirement of smaller land parcels, less input-intensive nature, and a source of regular cash income for the family.Poshan Vatika

Introduction (Why)

It is ironic that the ones responsible for ensuring food security for a vast country like ours, most often sleep with empty stomachs. The households of small and marginal farmers have the highest rates of malnourishment in the nation. According to a study (Biswabhusan, Sahoo, & Suar, June 2020), 50.4% of rural households remained chronically food insecure throughout the year. The Global Hunger Index 2020 places India 94th out of 107 countries, way behind Bangladesh and Sri Lanka in terms of malnutrition. We have the highest rate of anaemia in the world with around 40% of the anaemic population as per the lasted NFHS-5 survey. Another disturbing finding of the survey is that 66.4% of women and 68.4% of children suffer from anaemia, which signals that the situation has worsened over the last five years. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have worsened the situation for an average rural household. Small and marginal farmers have had to bear the brunt of disruptions in the food supply chain with an inability to supply their produce to the market on the one hand and the unavailability of vegetable hawkers on the other. Another important element that COVID-19 brought forth was the concern over boosting immunity. Studies showed that people with better immunity had fewer chances of getting dangerously ill from the SARS-CoV-2. Health advisories suggested the inclusion of fruits and vegetables in the diet for improving immunity. Most urban Indians had little trouble procuring vegetables, due to an ample number of vegetable hawkers providing street to street service. It was crucial to ensure the same for rural communities. While people in villages had a tough time buying vegetables due to transportation difficulties, they had an asset that could be productively used to ensure a proper nutritional diet. Every rural household has homestead land which can be used for planting vegetables for household consumption. Kitchen gardens are a common practice in rural India but due to poor management and planning, most of them are temporary.Poshan Vatika (What)

During the COVID-19 crisis, SRIJAN emphasized the promotion of Poshan Vatikas or household kitchen gardens to make rural households self-sufficient in meeting their nutrition needs. A Poshan Vatika is an 80-100 square meter plot set up in the homestead land of a rural household that allows for the cultivation of 5-6 different vegetables and provides enough food for consumption all year round for a 5-member household. The shape of the poshan vatika can be rectangular or circular based on the availability of resources and the choice of the farmer.Poshan Vatika (How)

- Land Selection

- Land Preparation

- Raised beds preparation

- Selection of vegetables

- Sowing

- Irrigation

- Nutrient Management

Land Selection

A small land parcel located near the house, which has fertile land, and easy access to irrigation all year round is preferred for the development of the kitchen garden.Land preparation

The first step for developing a kitchen garden is the rejuvenation of land before the sowing of seeds. This is mixing the soil with equal parts of organic fertilizer such as farmyard manure or ghanjivamrit. Trichoderma powder is used to minimize pests.Raised Beds preparation

The kitchen garden plot is then divided into 6-8 raised beds of equal size to cultivate different types of vegetables. Raised beds with channels between them are good for vegetable cultivation as most vegetable crops need water enough to allow moisture management. Raised better allow for better drainage of water and are easy to maintain.Selection of vegetables

This is the most crucial step for developing an evergreen Poshan Vatika which provides vegetables throughout the year. Selecting the right crop combination is crucial as the crops selected should complement each other in terms of nutrient and space availability. Crop planning is crucial for the success of a Poshan Vatika. Crop planning should include the following elements:- The layout of the beds

- Selection of compatible crops

- Season of sowing

- Resowing guidelines (what, when)

- List of different suitable crop combinations

A good strategy is to grow crops of varying heights and different harvesting cycles. For instance, a poshan vatika that grows tubers such as onions and ginger, herb crops such as spinach and coriander, small-height crops such as tomatoes, eggplants and creepers of the gourd family; is not only using vertical space more effectively but also allowing for staggered harvests throughout the year. Herb crops such as spinach can be harvested after two months only, while tomatoes, eggplants and creepers after 4-5 months, and tubers after 6-8 months.

Another important element is re-sowing at strategic intervals to replenish beds that have been harvested. Important considerations while re-sowing are crop rotation and cropping of compatible vegetables.

Sowing or planting

After the crop selection has been done, sowing is undertaken. For most vegetable crops, it is a good practice to prepare seedlings and then transplant them in the Poshan Vatika bed. The best season for sowing vegetables is either June-July or during February-March, as these are the periods when the soil-moisture level is good. Other possible options are August-September and October-December.Irrigation

Providing water at crucial stages of crop growth is crucial. As most Poshan Vatikas are set up on homestead land, they can make good use of household wastewater that is used in the kitchen or for other purposes.Nutrient Management

Vegetable crops need proper nutrient recycling to produce a good harvest. Regular manuring especially before flowering and fruiting is crucial for optimum production. SRIJAN builds the capacities of farmers to make organic fertilizers such as Dhruv jivamrit, Jivamrit and growth stimulants such as soya plant booster using locally available materials, cow urine and dung. The organization has also promoted natural farming units at the village level which enable easy access to these organic inputs.

Possible combinations for Poshan Vatikas

| Plot no. | Vegetable crops |

| 1 | Potato, Cauliflower |

| 2 | Cauliflower, cabbage |

| 3 | Cabbage, varieties of beans |

| 4 | Peas, okra, |

| 5 | Cauliflower, cabbage, Radish, onions |

| 6 | Eggplant, Spinach |

| 7 | Brocolli, spinach, beans |

| 8 | Carrot, okra, cucumber |

| Bunds | Tubers like carrots, radish, beetroot |

| Border | Creepers of the gourd family, |

Reach (Where)

Poshan Vatikas have been promoted extensively in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh by SRIJAN. 5843 farmers have developed Poshan Vatikas in their backyard.Cost and Benefits

The total cost to set up a Poshan Vatika is under Rs. 1000. 50% of the amount accounts for farmer’s contribution in the form of homemade organic manures, labour for bed preparation, bamboo and wire for wooden trellis, etc. The household can produce 7-12 types of vegetables and can harvest 1-1.2 quintals of fresh vegetables during a year, thereby having easy access to fresh vegetables and leading to savings to the tune of Rs.5000-7000 incurred on procurement expenditure.Major Learnings

- It is important to select the beneficiaries with care, as the poshan vatika promoted needs proper care and time management to yield vegetables all year long. It was noticed that some beneficiaries who did not resow at strategic duration during the year did not have the desired harvests.

- If the poshan vatika was maintained well, its yielded surplus harvests which some families sold in the market. Even after using for domestic consumption, some families could sell vegetables worth Rs. 5000-10,000 during the year.

- Development and maintenance of proper raised beds proved to be a crucial practice. It was observed that some kitchen gardens which had improper beds suffered losses during heavy monsoons.

- The need was felt to have proper modular training material on pest management through natural means. As a variety of vegetables were planted, each had different types of pest management needs.

Scale-up potential

Poshan Vatikas or Kitchen gardens are a common practice in most rural villages. The value addition that SRIJAN has provided is in the improved layout, design and package of practices. Kitchen gardens which provide enough produce to meet the consumptive needs of a household round the year are crucial to ensure the nutritional security of a rural household. Infact, the Union government launched Poshan Abhiyan post the COVID-19 lockdowns worsened the conditions of rural areas. Under the programme, the union government outlined the guidelines to develop Poshan Vatikas, which encouraged communities to cultivate local nutritional food crops and vegetables in their backyard. Since March 2020, there has been a landslide movement, wherein several CSOs and NGOs across the country have encouraged communities in their working areas to develop Poshan Vatikas. The exact numbers of Poshan Vatikas developed during the last year is not available as it has been an initiative led by various NGOs, government departments and even individuals, but the numbers have been substantial and the cumulative efforts of many have resulted in ensuring nutritious food for rural households.Miyawaki Forests

Introduction (The Why)

Villages in India were traditionally known to have adjoining forest areas and grasslands which were used by them for grazing their cattle and goats, collecting non-timber forest produce, forest vegetables, and fuelwood for domestic consumption. Colonization robbed India of most of its diverse natural forests and brought in an era of monoculture, wherein large desolated teak forests were grown on a large scale to meet the timber needs of the East India Company. Even today, the working plans of forests are prepared, based on the same crooked wisdom passed on by the Britishers. And for most forests that are not protected, the fate is mostly gradual degradation into a wasteland. Villages today no longer boost forested hills but rather denuded and degraded slopes of land. The rains that most farmers rely on for their Kharif crop are quickly washed down these denuded slopes, and even during a good rainfall season, most wells go dry a few months post-monsoon, as groundwater recharge is minimal. Gone are the days, when forests and vegetation used to break the flow of water and simultaneously recharge the village wells. The dissociation of agriculture from forests and the accompanying ecosystem have turned agriculture into a seemingly unfeasible venture. Improving the forest and tree cover in rural areas is not only important from the broader perspective of improving overall forest cover in India but also imperative for developing climate resilience in agriculture and livestock.Miyawaki (The What)

Miyawaki is a technique that helps build a dense native forest on a small plot of land. It was pioneered by botanist Akira Miyawaki in Japan in the 1980s and since then Mr. Akira has planted 40 million trees have been planted using his method in more than 15 countries around the world. This approach calls for 30 times denser plantation than usual and the plant growth is 10 times faster. Miyawaki forests become self-sustainable within 3-years of the plantation. Miyawaki proposed that it was possible to create a forest within 20-25 years by replicating the characteristics of a natural forest. His visits to Shinto Shrine forests along with his studies in phytosociology (the way different plants interact with one another) led him to the understanding that indigenous forests had four distinct categories of plants; canopy, tree, sub-tree, and shrubs. Using this knowledge, he developed his own system of planting forests, which is now widely recognized as a potential solution to quickly arresting deforestation. In India, Miyawaki is seeing good adoption in urban areas as this method fits in perfectly with the city landscape. As land is scarce in cities, the Miyawaki approach offers a good solution. Currently more popular in South Indian cities, the concept is slowly picking up due to the interest of municipalities and environmentalists. SRIJAN is one of the first grassroots organizations to see the potential of Miyawaki in creating and reviving village forests. The organization is promoting Miyawaki as part of a larger Climate-Smart Agriculture strategy. A micro-level approach, it accommodates both cost and time constraints of grassroots programmes.How to set up a Miyawaki forest

- Site Selection

- Formation of Forest Management Committee

- Selection of species for plantation

- Land preparation

- Designing the forest

- Tree plantation

- Monitoring and maintenance

1. Site Selection

To set up a Miyawaki forest, a village with an active community that has demonstrated interest in and adopted other activities undertaken by the organization is selected. To set up a Miyawaki forest, common land is preferred. Panchayat lands and private lands can also be considered if the necessary permissions are obtained, and if the site has been used by the community for a common purpose. The area requirement for setting a Miyawaki forest of 1200 plants is 500 sq. mt. Sites such as temple compound, Shamshan ghat (cremation land), etc. are given priority. The purpose of developing Miyawaki forest is to restore the forest ecosystem and its associated services (reducing erosion, maintaining water cycle, improving water retention, and groundwater recharge). It is therefore important that the community does not harvest firewood and fell trees of the forest, so developed. It is therefore pertinent to select a site that has a religious attachment which could go a long way towards ensuring its protection in the long term.2. Formation of Forest Management Committee (FMC)

This is one of the preliminary processes to set up a Miyawaki forest in the village. Post the interest and willingness of the community have been established, a forest management committee is set up comprising of 12-15 community members in a general village meeting. Care is taken to include people from all castes, religions, gender, and economic backgrounds. The committee is tasked with coordination of overall efforts of setting up the forest; planning, land preparation, procurement of plants, community participation in plantation, regular watering, and eventual maintenance of the forest established.3. Selection of species for plantation

A list of all the native species which grow in nearby forests is prepared. Species of medicinal and herbal use such as Neem, Amla, Harra, Behera, etc. are given preference. Species with good timber value are avoided to detract felling and exploitation. The following are considered for developing a species database:- Identify species type (deciduous or perennial) and its maximum height.

- Search the nurseries nearby for the availability of saplings, their age, and sapling height. The ideal height is 2-3 ft)

- Identify 5 different species as the major species of the forest to be set up. These should be species found in the nearby forest area. These will make 40-50% of the forest.

- Identify 15-20 other species which will be planted as supporting species. These will make 25-40% of the forest and other minor species will make up the rest.

| # | Species | Common name | Type | Benefits | Height | Layer | Availability |

| 1 | Azadirachta indica | Neem | Evergreen | Medicinal | 25 mts | Tree | Yes |

| 2 | Syzygium Cumini | Jamun | Evergreen | Fruit | 35 mts | Canopy | Yes |

| 3 | Punica granatum | Pomegranate | Perennial | Fruit | 8 mts | Sub-tree | Yes |

| 4 | Jasminum sambac | Jasmine | Evergreen | Flower | 3 mts | Shrub | Yes |

4. Land Preparation

It is one of the most crucial aspects of developing a Miyawaki forest. As a very dense plantation model is followed, the soil must be fertile and have proper nutrients and porosity. The first step is the removal of weeds and other debris from the soil. Post this, the soil is dug to a depth of 3 metres, and the excavated soil is kept aside. Four key elements are added to the soil to improve its texture, water retention, porosity, and richness. Perforators such as rice husk, wheat husk, corn husk, etc. are added to improve the porosity of the soil which allows roots to grow quickly. In a 500 sq. mt. land, 20 trolleys of husk are needed. The FMC arranges for the required quantity of husk from the village community. Water retainers such as coco-peat or dry sugarcane stalks can be used to improve the moisture retention capacity of the soil. Organic fertilizers such as Farmyard manure (FYM), Jivamrut, etc. are used to improve the quality and richness of the soil and promote microbial and earthworm activity. 20-25 trolleys of Mr and 200 litres of Jivamrut are needed. Mulch - The forest floor is always covered with dry leaves which protect the soil from direct sunlight. It is therefore that dry leaves are needed to cover the newly enriched soil of the miyawaki forest too. 3-4 trolleys of dry leaves are needed for a plot of 500 sq. mt. The husk, coco peat, farmyard manure, and Jivamrut are mixed with the soil and the mixture is spread uniformly on the plot.5. Designing the forest

This is an important step in setting up a Miyawaki Forest. As a Miyawaki forest is to resemble a natural forest that has four levels of plants, i.e. Canopy, trees, sub-trees and shrubs, it is important to plant trees in a similar assemblage. The species to be planted as identified in the previous step are assigned one of the four layers stated above. The plants are divided into Canopy trees, which would form the topmost layer, followed by Tree, Sub-tree and Shrub species. The identified species are planted in circles. For example, Circle I would have 1 canopy tree in the centre forming the first layer, surrounded by 3-4 trees forming the second layer, covered by 7-8 subtrees forming the third layer, and ultimately 10-12 shrubs in the outermost layer. Similarly, Circle II will have a different formation, of trees, sub-trees and canopy trees. The aim is to group plants that grow into different layers in each square meter and to have a random dense plantation of native tree species. While all four layers will be present in a circle, their positioning can vary. It is therefore important to not stick to any one pattern of planting trees. As it is a dense plantation model, the plant to plant and circle to circle spacing is 70 cm as opposed to a conventional plantation which has a spacing of 6 feet for higher.6. Plantation of Trees

Once the required species and number of trees have been procured from a local nursery, the plantation date is decided mutually by the FMC in a village meeting. Active community participation for plantation is sought. On the stated day, the community members get together and prepare the land for the plantation as mentioned in step 4 above. The inputs required for improving the soil as mentioned above are gathered by the FMC from community members. The trees are planted as per the design mentioned above (step 5). To plant a tree, a small pit is dug, and the plant is removed from the plastic potting bag. The plant so removed is dipped lightly in the Jivamrut solution and quickly placed in the pit. The outside soil is levelled gently around the tree. Post planting the sapling, it should be staked using bamboo sticks. 1200 bamboo sticks are required to stake 1200 saplings on 500 sq. mt. plot. The preferred height of saplings procured is between 2-3 ft. and the plant to plant spacing to be maintained is 70 cm.

7. Monitoring and Maintenance

The maintenance and monitoring of the forest established is entrusted with the FMC. Committee members and interested community members prepare a rotational rooster to water the plants every day. Weeding is also done once or twice a month in the initial year to ensure the plants get the best chance to grow. Cutting or pruning is never done in a Miyawaki forest as the aim is to replicate a natural forest nor is any organic matter or leaves removed from the forest floor. On the contrary, the plantation site needs to be re-mulched for atleast the first year until the trees are big enough to provide an ample supply of dry leaves. After the initial mulching is done on the plantation day, dry leaves need to be collected and spread on the forest every month. The monitoring of the miyawaki forest is done by the FMC to note its growth. The length of the saplings is noted at the time of plantation and it is reassessed every 6 months to monitor the growth rate. Similarly, the total number of saplings need to be recorded every six months to assess the survival rate.Reach

SRIJAN initiated working on the village Miyawaki forests, coined as ‘Tapovan’ in August 2020 and has established 3 Tapovans since the last year in Chittrakut and Tikamgarh districts of the Bundelkhand region. The initial response from the community is promising with a 97% survival rate. The trees in the Tapovans have reached a height of 10-12 feet within the first year.Cost and Benefits

The best thing about Miyawaki forests is that there is almost no recurring cost and the forests become self-sustainable within 3 years. The total cost of setting a Miyawaki forest of 1200 trees on 500 sq. mt. of land is Rs. 2,00,000. A major cost component is the saplings which have to be procured from the nursery. An advantage of establishing miyawaki forest in rural areas is that the material needed for land preparation such as husk, FYM, jivamrit and leaves is readily available in the village. The cost of these inputs is thus not included in the estimate. Community members voluntarily contribute the labour for plantation and efforts are made to plant all trees in a single day to ensure maximum participation from the community. As the initiative is very recent and the Miyawaki forests set up are just a year old, it is difficult to state the benefits incurred. Within a year the trees have grown three-four times in height which is tremendous growth. Also, 97% of the saplings have survived and as the saplings are already well established, the survival rate will not be affected further. These observations are promising. One thing which can be said with confidence is that given the growth rate of Miyawaki forests, the community members will reap the benefits of the fully-grown Miyawaki forests within their lifetimes.Major Learnings

- Promoting the Miyawaki forest as a sacred grove has seen greater participation from the community, and it also led to better protection.

- The species planted in the Miyawaki forest should be native to the locality. This is of utmost importance as it is not certain what impact the exotic species might have on the forest if introduced. It is therefore important to have a botanist in the field team

- Community participation is of utmost importance to not only ensuring the sustainability of the forest but also its development. In rural areas, a large amount of cost and hassle is saved as the material for land preparation such as husk, farmyard manure, jivamrit, ghanjivamrit, dry leaves for mulching, etc. can be procured by collective efforts of the community.

- Involvement of government officials from the start helps with procurement of necessary approval in case of government-owned land, along with that it also leads to wider replication of the initiative.

Replication and Scale-up Potential

The government of Telangana has taken the lead in the adoption of the Miyawaki method of plantation to revive deforested areas near villages as well as in cities. It has issued a guideline encouraging Miyawaki’s adoption by various government and non-government bodies. Maharashtra state government has set up a panel to understand the potential of Miyawaki for afforestation. Based on the recommendations of the committee, the state might issue guidelines to promote Miyawaki. Apart from the government’s initiatives, Miyawaki forests are mushrooming all across the country under small independent projects by environmentalists and city municipalities. Bangalore, Chennai, and some other South Indian cities are amongst the forerunners of these afforestation drives. Some notable startups that are providing technical support for setting up Miyawaki forests are Afforest, Thuvakkam (Chennai), and Say Trees (Bengaluru). Afforest has planted 4.5 lakh trees across their 108 projects; ninety of these sites are located in India. Say Trees engages with citizens and corporates and has helped plant 70,000 trees in Bengaluru from 2008. From Miyawaki’s inception of these high-density forests in the 1980’s, the concept has seen wide-scale adoption in many countries. Miyawaki, even today, at the ripe age of 90 is active in setting up these micro forests around the globe. In the last 4 decades, Miyawaki alone has afforested 40 million hectares of area with Miyawaki forests.Soya Samriddhi Model

Introduction (The Why)

Agriculture is the mainstay of the majority of India’s population especially for the people living in villages. Rural India is predominantly agrarian. 80% of households in rural India depend upon Agriculture for their livelihood. Infact, India has the highest land area under cultivation despite having much less geographical area than the USA, China and Russia. Despite this fact, our crop productivity is lower compared to that of developed nations. An important factor contributing to low farm productivity is the rainfed nature of the majority of landholdings. Nearly 50% of India’s arable land is rainfed, which makes returns from agriculture as uncertain as to the rainfall that it depends upon for irrigation. Apart from this, there are other important factors that lower productivity which fortunately are controllable. Some of these factors are lack of knowledge regarding modern technologies, lack of availability of quality seeds, poor knowledge extension and lack of investment. Due to the unavailability of credit at reasonable rates, most farmers borrow sub-optimally as the interest rates charged by private moneylenders are exorbitant. Women are most often involved in most of the labour-intensive farming work, but due to a lack of control over finances, they do not have adequate knowledge about markets. Improvement in agricultural productivity can be enabled if all the above factors are addressed. The main areas where targeted interventions are needed are; access to quality inputs, access to finance at reasonable rates, knowledge extension on best package of practices, and market facilitation.Soya Samriddhi (The What)

Soya Samriddhi Model conceptualized by SRIJAN to improve the productivity of rainfed small and marginal Soyabean farmers of Bundi district in Rajasthan is based on four key pillars;- Access to quality inputs including seeds, fertilizers, appropriate equipment

- Access to finance at reasonable rates through the medium of Self-help groups of women that mobilize savings and help women purchase agricultural inputs through inter-group lending.

- Knowledge extension to farmers: Capacity building and training of women farmers on best package of practices for a particular crop in regards to soil preparation, seed treatment, fertilizer application, weed management, pest management, Irrigation, and threshing operations, was undertaken. Intensive training was given to select women farmers who later became ‘Krishi sakhis’, or community resource persons for the farmers of their village by disseminating the best practices to the fellow farmers of their villages.